/afaqs/media/post_attachments/b98913ef9a8cfc21525fda7de57fc2e3a9f7d96eb27ac89aef6c61b05e8f6c15.jpg)

Driving into unfamiliar territory is often fraught with uncertainty. Many brands, however, have moved off their regular path to target a different audience.

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/bded8f33f1ae1250234aec3e2a7e0bbe48d2cd564b5f9f9bd3b52da621f0f9e5.jpg)

Brands do change focus - sometimes when they are well into their lives. It could have to do with a change in target audience, roping in an unexpected set of consumers, coming up with a new positioning plank or redrawing the portfolio of offerings. Consider this example from the past. In 1924, Philip Morris & Co. introduced Marlboro as a woman's cigarette. And the communication designed was targeted at the fairer sex.

A few decades after its launch, Leo Burnett's bright idea of turning things around gave the world the legendary Marlboro Man. From 'Mild As May' to the rugged, masculine smoker, the transformation was a stunning one, as was the success that followed. Not every brand has such a drastic change story to tell. India has its fair share of examples, successful as well as botched ones.

Change begets change

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/4857ea24c4a342e49643a9b62a9a951bb8bfe67730b1e770f0a7cb146c910cef.jpg)

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/75e9f8a690e768f43aaf5037ae8cc078a39be500a10d6d91be65806e40b30095.jpg)

At one level, it is important for a brand to change its look or message in order to stay relevant in a society that is never dormant. People change, as do their habits. It is the same with brands. But there are risks attached.

When Cadbury decided that it did not want to get stuck continuing to talk to children, was it a cakewalk? Or, when Lifebuoy tried shaking off its image of being a men's health soap, did it hurt? There are enough concerns on a brand manager's mind as he looks at newer vistas. One cannot just hop and change tracks as and when one pleases.

"The prime objective to expand one's target group is to ensure that the brand moves strongly in its growth trajectory. The new target segments add those extra muscles," says independent business strategist, Anirban Chaudhuri. Going back to the example of Cadbury, here is a brand that has constantly kept reinventing itself and adapting to the changing society around it. It smartly marries its own needs to grow as a brand with the same.

When asked, Abhijit Avasthi, national creative director of Ogilvy India - someone who has closely worked on Cadbury - says, "Anything that a brand does is to increase sales, gain market share and gain newer consumers for its products. There do exist roadblocks at different stages and that is when brands start looking at things differently."

Sweet success

The Cadbury story is simple and interesting. One of its initial roadblocks was to take a product primarily seen as an urban children's delicacy to the adult. It was not as if grownups did not enjoy a chocolate treat. Thus arrived 'The Real Taste of Life' campaign in the early '90s. It cleverly said there is a child in all of us, bring it out and enjoy the chocolate. Can one forget the cricketer's girlfriend throwing caution to the winds and dancing on the cricket field in joy?

Cadbury then decided to move to the masses. The product was repackaged. Smaller variants were introduced at a lower price making the product more accessible and the tone and manner of the communication again changed with Khaane Waalo Ko Khaane Ka Bahaana Chahiye setting the trend of 'massifying' the consumption of chocolates.

The brand then hit upon the insight of how a chocolate is a dessert too. In the sweet-loving country that India is, it threw up enough reasons to think of chocolates when it was time for guests. To highlight this, Cadbury launched the Kuch Meetha Ho Jaaye campaign. "It was about making the emotional value of happiness relevant to different audiences at different points in time," sums up Madhukar Sabnavis, country head, discovery and planning; regional director, thought leadership, Ogilvy India.

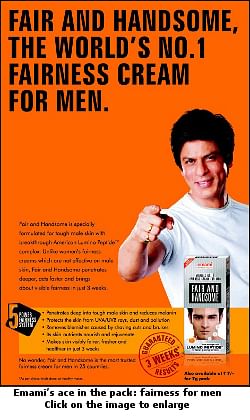

Another category that embraced change was grooming products. Long targeted at females, there began a sudden mushrooming of fairness creams - and other grooming material - led by Emami. Dheeraj Sinha, head, planning, South and South East Asia, Grey explains, "Looking good was becoming important not only in the workplace but also in the dating market."

Options galore

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/f2d283f1b4f300731756f67a8fab8c01919d72a39907dde880b332afe47f1fd0.jpg)

A brand may have a variety of options to choose to further its segmentation strategy. While keeping the product line same and changing the tone of communication is one, brands often tend to introduce variants that piggyback the mother brand's equity while communicating to a new set of audience with a new, relevant offering.

"Introducing variants for different groups is a useful way of extending into newer segments because there is some amount of equity that a brand has acquired and you are just stretching it into different ways," notes Anand Halve, co-founder, Chlorophyll. A case in point is Horlicks. The malted milk hot drink from GlaxoSmithKline ventured into various sub-brands created especially for segments - women, children and the elderly.

Swati Bhattacharya, national creative director, JWT India, has been among the ones who led the brand's changed stance in the early 2000s. "Horlicks started out being a family nourisher. When I came on to the brand, we tried to make it a kid's brand. That is the time we did the Epang Opang Jhapang campaign! Horlicks was not seen as a kid's brand before that." Now, there are variants like Horlicks Lite to serve the nutritional needs of adults, Women's Horlicks, Mother's Horlicks (for pregnant and breastfeeding women) and Junior Horlicks for young children. Horlicks moved into other product categories like biscuits and noodles (the jury is still out on this one) too - riding on the health premise of the mother brand.

Lifebuoy, once synonymous with the red cake of soap, extended itself to break into upscale homes. The picture was no longer that of the grime-covered man in the bath with a germ-killing carbolic soap after a football match. Families now had Lifebuoy hand and body washes. But the promise of an ace germ fighter was not forgotten.

User-led change

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/43a691c067a173972935c8ab7d95ec2fcee7d4cacd4ed73ac3d156095fc40ff1.jpg)

/afaqs/media/post_attachments/738cf69a7ca334b6aa2931bcff97a8520bc480182c9ae335baece44134f58077.jpg)

Often, a shift in TG could just be a function of usage. The brand does not have to do anything except identify the opportunity and capitalise on it. Take the recent shift in BlackBerry's stance. BlackBerry phones have always carried the aura of belonging to the hotshot business executive connected to his office on the go. He checks mail while on the run, replies immediately signing off with the famous signature - Sent on my BlackBerry, surfs the net on his phone promptly and so on. It was all dandy till someone noticed that a feature called the BlackBerry Messenger was becoming widely popular with the youth.

BlackBerry did not change the target group. The product feature brought in a different set of users and BlackBerry just followed it. "A usage-based target group can be changed and is perfectly acceptable because the usage is leading the change and not the perception change that is involved," says Halve. Krishnadeep Baruah, director, marketing, Research in Motion agrees. "Four years ago, social media - led by the youth - was really picking up. We had a product that allowed the user to connect through various mediums - unique applications like BBM or popular ones like Facebook and Twitter. I think that was one big insight into how we moved into the youth segment," he explains.

It wasn't a walk in the park for BlackBerry and there was a lot of tailoring to be done. Curve, a new model, was introduced to make it affordable to this new target group. It also worked closely with its carriers to make data plans affordable. Alongside, it also relooked its existing segment that saw how the product could be used beyond official purposes. Remember Vodafone's widely popular 'We are the BlackBerry Boys'?

The caveats

One of the biggest concerns, as a brand extends itself to a new audience, is that of relevance. Packaging the same product and message and hoping it would ring true with a set of consumers that is probably completely different from the existing is foolish. Being relevant is the key.

Horlicks, in its various avatars, made sure that it sold a product to a group who would find it useful. Cadbury gave enough reasons for everyone to relish a chocolate. BlackBerry did not shy away from the fact that it could not go to a college student with a phone that would cost a year's pocket money. Lifebuoy knew that just a carbolic soap would not find favour in an upscale family.

Balancing multiple TGs is a challenge. "The key is to look at the need. And not every brand can do that," says Chaudhuri. The other concern is the risk of dilution of the brand. Each segment's needs may have been take care of, but has the brand been careful enough to keep its core value consistent all the way through? A brand builds equity over years and years of serving a consumer. Sometimes, if more is chewed off than what can be swallowed, there is confusion. "Why is my health care product offering me beauty options?" "Where has that one thing I got from my brand disappeared?" These are questions that have to be addressed.

Sab TV, the comedy channel from the MSM stable learnt it the hard way. In 2005, when the latter acquired the channel from Shri Adhikari Brothers, it repositioned it as a regular, second-rung general entertainment channel within the network. The move backfired but it went ahead and re-positioned itself, first as a youth entertainment channel and then experimented with cricket. In 2007, it went back to being a comedy channel. Back where it belonged, Sab TV has revived itself quite spectacularly.

Stay true

Brand value dilution is a big threat one must take into account when segmenting. Or, one might suddenly end up having a portfolio, which is wide but without any links. For example, when Mirinda introduced lemon, it jarred a bit. But since it is an impulse category, the brand can somehow get away with it. A slightly higher-involvement product might have had a bigger problem," declares Saji Abraham, vice-president, planning, Lowe Worldwide. Abraham chooses to talk about Lifebuoy, a brand that witnessed the shift that it did with Lowe.

"What we knew was that the male sportsman's soap needs to now appeal to the mother. So what are mothers concerned about? It is the family - the children. One of the first ads we released was for stomach infection. The doctor in the ad said it was not about what the child ate but the germs on the hands which, when ingested, cause illness. That changed everything. This was a time when Lifebuoy faced stiff competition from many beauty products. We could have removed the carbolic part and inserted some beauty oils to compete on level terms. But then we would have abandoned what the brand stood for. We would have been operating on what competition was forcing us to do. We took what the brand stood for - health - and interpreted it for a different TG. That is how we kept it relevant."

Horlicks too had to be careful. "A brand cannot do something that is completely different. If Horlicks brings out something that is only taste without the health edge to it, there will be a problem," opines JWT's Bhattacharya. However, not every brand needs - or wants - to change. Brands like Santoor soaps, Bournvita or Complan kept their TG consistent, as competing products chose to expand. Nirma stayed steadfast except for a brief while in the '90s.

The brand, known for its competitively-priced detergent, entered the carbolic soap segment with Nirma Bath Soap hoping to ride on the success of the former. Around the same time, it also launched Nirma Beauty Soap, once again a competitively-priced product in the beauty soap category that even successfully countered competition initially. This was followed by a couple of scouring products. Interestingly, Nirma also introduced edible salt - Nirma Shudh Salt. The diversifications didn't do much for Nirma - the audience wasn't prepared for a salt or a beauty soap from Nirma.

Watch out

If a brand really wants a change, there are pitfalls to watch out for, depending on what it is setting out to do. If a premium brand wants to talk to a mass audience, there is the risk of losing the cr�me de la cr�me consumer who will be miffed at not owning an exclusive brand anymore. A premium BMW owner might scoff at having to share the brand ownership with someone who just picked up an entry level Beamer. "The trick is to manage both. The guy who spends 100 bucks on a product should feel as good about buying the product as somebody who has paid 60 bucks. It is a tricky exercise," says Avasthi.

BlackBerry's Baruah suggests: "Continue to work on your mass offering and maintain that exclusivity at the high end." BlackBerry continues to aggressively market the Curve and Bold ranges while, at the same time, introducing the Porsche Design, a premium phone priced at over Rs. 1 lakh.

There is no foolproof recipe for a successful transition. But what should be of primary concern when a brand shifts its TG is not to abandon its existing segment, perhaps. In the effort to gain new markets, it cannot afford to alienate the existing ones.

/afaqs/media/agency_attachments/2024-10-10t065829449z-afaqs_640x480.png)

Follow Us

Follow Us